Lamb, K J, Launder D & Greatbatch, I.

The operational landscape and responsibilities of fire services throughout the world have changed dramatically over the last 15 years, with terrorist attacks, extreme weather events and complex changes to the built environment all greatly affecting the scope, severity and predictability of incidents attended (REFs). This places a tremendous pressure and responsibility on all Fire Officers.

It is recognised that firefighters and importantly Fire Officers must be more than just technically proficient. Strategic level fire officers in particular, operate infrequently, in low time, high-risk environments where fatalities and injuries are consistently linked to decision errors, with their decisions and actions of their organisation open to scrutiny during coronial proceedings. Therefore, improving the safety of emergency services personnel and importantly the communities they serve, requires the development of both technical excellence and decision-making in tandem.

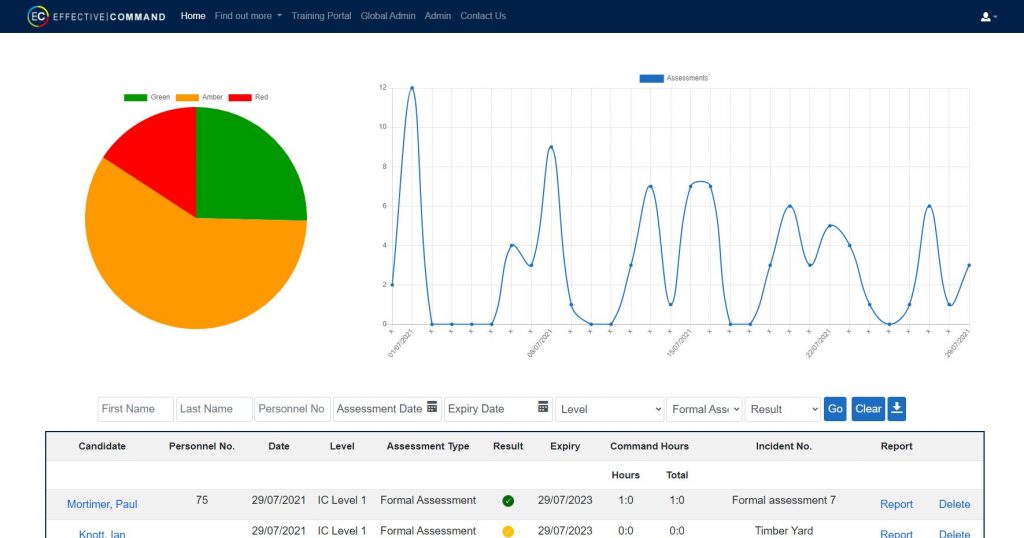

Command competence was assessed during training, assessment and monitoring events across all managerial tiers, using the Effective Command recording application. This application documents scores across several elements, during or after each training exercise, as a result of specific actions or considerations throughout each stage of an incident management cycle. These actions, and their outcomes consist of numerous individual elements such as the collection of initial information using relevant channels or accurate assessment of incident complexity. These are then categorised into red, amber or green through a standardised peer assessment.

The Effective Command tool has been in use for the last 4 years and data has been collected from over 1200 separate assessment events, across 4 continents, and at all 4 command levels (operational, tactical and strategic). It has been analysed and presented using standard statistical techniques and packages, giving insight into patterns and trends within approaches to command, differentiating between different nations, individual brigades, ranks and levels of command. Our assertion is that these trends, viewed longitudinally, help to illustrate potential future opportunities and requirements in training, with particular focus at the strategic tier. The interpretation of this data allows accurate development of future training programs which addresses the changing landscape of an already dynamic sector, importantly to provide documented records of command competence across all managerial tiers, and the consequential organisational assurance of its personnel.

Firefighters are required to make decisions under immense pressure, with the consequences of poor decisions including loss of life, property, critical infrastructure and economic and environmental loss (Arbuthnot 2002). Firegrounds are often hostile and rapidly changing and comparable to battlefield conditions, often comprising of significant levels of noise, emotion, smoke, flame and risks both obvious and hidden. Like the military, emergency service personnel must make decisions in high-risk situation (lives on the line) with very little time to make these decisions (for example, Klein 1998).

Unsurprisingly, within this context wrong decisions can sometimes be made. In the United States, errors of decision-making have been linked to approximately 30% of firefighter injuries and fatalities (Moore-Merrill et al. 2008). Several Crown inquiries/investigations in the UK and every major coronial investigation in Australia in the past decade have also identified decision errors as factors contributing to the deaths of firefighters or members of the public (for example Doogan 2006; Johnstone 2002; Schapel 2007). This is hardly surprising given the speed with which decisions are made on urban fire grounds where it is estimated that officers make 80% of decisions in less than one minute (Klein 1998, 2003).

Despite this, few fire authorities teach their personnel about decision-making, or how to make more effective decisions (Ferguson 2002). They may be reasons for this. We often hear that officers do not like the idea of teaching firefighters to make decisions because they may be less likely to follow orders. This demonstrates a belief that junior personnel should concentrate on learning firefighting techniques at this point in their career. We have heard officers express concerns that teaching decision-making will be in conflict with the organisation’s policy and procedures. However, a more far-reaching problem is that the training syllabus provided by most fire authorities is content-based rather than behavioural. Where this model exists, personnel are taught lots of ‘stuff’ (content out of context) without necessarily being taught how to use what they have learned. There is often a preponderance of “facts and figures” (for example the weights or heights of pieces of equipment, which are easy to assess quantitively, but arguably of little practical operational value.

Teaching content without context or behaviours may be of particular concern in the high-risk emergency services industry. An individual could learn the technical aspects of fire behaviour, including flashover or backdraught conditions, without developing any practical competence from this form of training. Knowledge of facts is only a small component of learning or expertise. Rather than simply recalling knowledge, highly skilled experts apply knowledge in context. Bloom’s hierarchy (or taxonomy) outlines six levels of knowledge, these are:

- Knowledge: most simply the ability to memorise, recall, or reproduce learned information on demand.

- Comprehension: the ability to do something with knowledge such as; describe, explain, identify or locate and recognise important cues or information.

- Application: the ability to apply or use knowledge in a meaningful way apply, for example to solve a problem.

- Analysis: the ability to deconstruct something and compare or contrast it with other knowledge or experiences.

- Synthesis: the ability to apply knowledge in new ways to solve problems. Includes developing plans or designing novel solutions.

- Evaluation: the ability to evaluate performance. Requires a clear understanding of good performance and its key elements as well as the ability to appraise, assess, compare, and judge.

An expert should be apply each of these levels depending on the context or situation. However, we believe expertise requires other key behaviours. The following section considers these behaviours in detail.

Defining firefighting expertise – the Effective Command philosophy

The Effective Command philosophy is that expertise depends on the ability to make sense of a situation, decide on a course of action, and then be able to execute that course of action to produce a satisfactory outcome. Effective Command focuses on five key behaviours employed by expert emergency responders and incident commanders (Launder and Perry 2014). Each of these behaviours has been defined and ‘unpacked’ through research. This provides a clear model of effective command behaviour that can be taught, learned and assessed. Effective Command also incorporates these behaviours into a framework that simplifies the process of developing training, assessment and operational review systems and tools. In summary form the five key behaviours are:

- Developing situational awareness (Endsley 2000) – situational awareness can be summarised as knowing what is going on around you’. More accurately, it involves ‘perceiving situational cues, understanding what is going on around you and accurately predicting future events’.

- Making a decision – making decisions is a critical part of fireground operations. Experts make decisions in a number of different ways. In the majority of cases, firefighters make decisions very quickly and without considering more than one option.

- Setting objectives (planning) – Effective officers clearly define what they want to achieve. Effective fireground plans are simple, with clear objectives that make sense, and translate into aligned strategies and tactics.

- Actions behaviours – These behaviours include the ability of an individual to perform technical tasks as well as the interpersonal abilities required to direct or task others. Effective commanders use communication, coordination and control to ensure decisions are safely and effectively implemented.

- Review – Experts constantly seek information about how the incident is progressing so that they can make necessary changes. Experts also learn from their experiences through critical reflection afterwards.

An efficient approach: developing firefighters and officers using the same behaviours

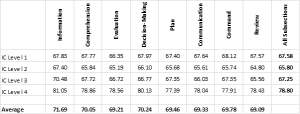

The Effective Command approach is to develop each of the five key behaviours across eight assessment sections in context at all levels of the command system. These are; Information Gathering, Comprehensive and Evaluation (assessing Situational Awareness), Decision Making, Planning, Communication and Control (Action behaviours) and Review. The assessment tools were used by a trained and standardised team of assessors within each organisation and documented the performance and rationalised decision making of candidates during a formal assessment of their command competence. The candidates were assessed following their management of an incident scene in either simulation or a practical scenario.

Within each of the assessment pages there are 9 sub-level criteria, which the assessment team use to score the candidates against regarding their decision-making behaviour/rationalised action, each criteria can achieve a maximum score of 5 for exceptional performance, with 3/5 deemed a satisfactory performance (see figure 1). The score is awarded based on how well each behaviour is demonstrated by the candidate and importantly the rationale of the key behaviours is explored through discussions between the candidate and the assessor.

The assessment tool covers all four levels of command as detailed within the UK fire Service.

| Assessment Tier | Command Level |

| Level 1 | Operational (in command of 1- Fire Trucks) |

| Level 2 | Operational (in command of 4-6 Fire Trucks) |

| Level 3 | Tactical (in command of 6-10 Fire Trucks) |

| Level 4 | Strategic (in command of 11 + Fire Trucks) |

Results

The Effective Command assessment tools are currently used for incident command training and formal competence assessments in UK, Portugal, Estonia, Dubai, Singapore, Australia and Canada. The data presented below was generated from over 1200 separate formal assessments at all four command levels, amassing over 88,000 separate data entries for each of the criteria. The training data wasn’t used during this analysis as the tools allow individuals to enter self-reflective entries on their own performance and is not standardised through any formal training.

Figure two: Data collated from 1200 separate assessments. Data presented represents average scores assigned for each phase of the decision-making process at all command levels. N=number of data entries for each level: Level 1 n= 69905, Level 2 n= 14130, Level 3 n= 3024, Level 4 n= 1224).

This data highlights areas of both strengths and weaknesses of candidates at all 4 command levels. The general inferences are that candidates at all command levels are much better at gathering information than they are at both comprehending the information gathered or anticipating its effect on the incident progression (evaluation phase). The area with the lowest overall score was the review phase, which correlates with the poor incident anticipation documented. In addition, the evidence presented shows a substantial dip in overall competence between level 1 and 2 commanders, which then steadily recovers, with the Level 4 commanders scoring the highest values across all phases of the Effective Command assessment. This could be attributed to a number of factors, including reduced frequency of training opportunities, significant increase in the incident complexity, lack of operational experience/exposure at growing incidents, further data analysis will be needed before formal recommendations are made.

Conclusion

In summary, we believe the Effective Command approach provides a safe and efficient way of developing and assessing incident management expertise and importantly the data tends identified can be fed back into subsequent training cycles to ensure continual organisational development. By employing a consistent behavioural framework, the process of developing essential knowledge and behaviours begins earlier and ensures firefighters are safer and more effective both immediately and as future officers. The behaviours developed through the Effective Command model have been identified as critical in the literature, coronial review and Royal Commissions. Their development significantly enhances the safety of operational personnel and the public and can be used as evidence that an emergency service organisation has learned from and addressed known risks to firefighters. This methodology has very efficiently generated evidence that can be readily be fed back into organisational learning, leading to an immediate impact Fire Officer development. Further analysis of this data will explore the specific behaviours that individuals failed to demonstrate when being validated for their Incident Command competence.

Bibliography

- Klein, G 1998 Sources of Power – how people make decisions. Cambridge: MIT Press

- Klein, G 2003 the power of intuition New York: Currency Books

- Moore-Merrill L, Zhou A, McDonald-Valentine s, Goldstein R & Slocum c. (2008) contributing factors to line of duty injury in metropolitan fire departments in the United States Retrieved xxxxxx from International Association of Firefighters.

- Doogan M 2006; inquests and inquiry into four deaths and four fires between 8-18 January 2003 Canberra ACT Coroner’s Court

- Johnstone G 2002 Report of the investigation and inquests into a wildfire and the deaths of five firefighters at Linton on 2 December 1998. Melbourne State Coroners Office

- Schapel AE 2007 inquest into the deaths of Star Ellen Borlase, Jack Morley Borlase, Helen Kald Castle, Judith Maud Griffith, Jody Maria Kay, Graham Joseph Russell, Zoe Russell Kay, Trent Alan Murnane and Neil George Richardson, Adelaide South Australian Coroners Office

- Ferguson E 2002 Leaders, managers and decision makers; the role of values-based decision making Australasian Fire Authorities Council Conference Gold Coast Australia AFAC

- Launder D. and Perry C., (2014). “A study identifying factors influencing decision making in dynamic emergencies like urban fire and rescue settings” International Journal of Emergency Services, Vol. 3, No 2, pp144-161.

- Endsley M R 2000 Theoretical underpinnings of situational awareness: a critical review. In Endsley MR & Garland DJ Situational Awareness Analysis and Measurement Mahwah : Lawrence Erlbaum Associates